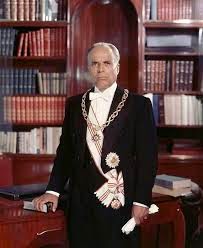

History of Tunisia :Bourguiba the GRAETEST leader but DICTATOR

Presidency

Bourguiba set about shaping the new republic in accordance with his

personal vision. In 1959 the Neo-Destour won all 90 seats in the new

National Assembly, and a constitution was introduced that made the

assembly solely responsible for rule and order in the country. The role

of Islam

in Tunisian identity was recognized, although the workings of

government were to be exclusively secular. Women’s rights were

recognized in the 1956 Code of Personal Status, an extraordinarily

radical document for its time that, among other things, banned polygamy, gave women virtual legal equality with men, enabled women to initiate divorce,

introduced a legal minimum age for marriage, and gave women the right

to be educated. Education was extended throughout the country, and the

curriculum was modernized to reduce religious influence. The military

was firmly subordinated to civilian government, and the administration

underwent a process of “Tunisification” to replace French workers with

Tunisian counterparts.

Bourguiba set about shaping the new republic in accordance with his

personal vision. In 1959 the Neo-Destour won all 90 seats in the new

National Assembly, and a constitution was introduced that made the

assembly solely responsible for rule and order in the country. The role

of Islam

in Tunisian identity was recognized, although the workings of

government were to be exclusively secular. Women’s rights were

recognized in the 1956 Code of Personal Status, an extraordinarily

radical document for its time that, among other things, banned polygamy, gave women virtual legal equality with men, enabled women to initiate divorce,

introduced a legal minimum age for marriage, and gave women the right

to be educated. Education was extended throughout the country, and the

curriculum was modernized to reduce religious influence. The military

was firmly subordinated to civilian government, and the administration

underwent a process of “Tunisification” to replace French workers with

Tunisian counterparts.An experiment with a collectivist form of socialism was abandoned in 1969. The World Bank had refused to fund the program, significant sections of the agricultural community had resisted it, and the experiment failed to produce the desired increases in output; in addition, Bourguiba became convinced that the program’s primary advocate, Ahmed Ben Salah, was using it to enhance his own ambitions. During the 1970s Bourguiba oversaw an export-oriented policy, fueled by domestic oil revenues, labour remittances, and foreign borrowing. When all three sources dried up in the 1980s, the country was deeply in need of investment finance. The private sector, which had been partially subsidized by the government but equally excluded from certain areas of production and price setting, was unable to fill the gap, and the country spiraled into debt-ridden crisis, finally turning to the International Monetary Fund for a structural adjustment program in 1986.

Bourguiba’s foreign policy reflected his preference for pragmatism over ideology.

He looked to the West for economic and military assistance, but that

did not prevent him from engaging non-Western countries in pursuit of

export markets and bilateral trade. He aspired to maintain a special

relationship with France, believing that there were positive economic,

cultural, and social legacies of colonialism to be exploited. Despite

major crises over Tunisian support for the Algerian liberation struggle,

a Tunisian attack on the French base at Bizerte,

and the expropriation of settlers’ lands, Bourguiba generally managed

to secure a Palestine Liberation Organization a base when it was expelled from Lebanon in 1982.

Bourguiba’s foreign policy reflected his preference for pragmatism over ideology.

He looked to the West for economic and military assistance, but that

did not prevent him from engaging non-Western countries in pursuit of

export markets and bilateral trade. He aspired to maintain a special

relationship with France, believing that there were positive economic,

cultural, and social legacies of colonialism to be exploited. Despite

major crises over Tunisian support for the Algerian liberation struggle,

a Tunisian attack on the French base at Bizerte,

and the expropriation of settlers’ lands, Bourguiba generally managed

to secure a Palestine Liberation Organization a base when it was expelled from Lebanon in 1982.lasting and cordial friendship between the two countries. He also worked tirelessly to develop good relations with the United States, being eager to link Tunisia in to the technologies of modernization. To the chagrin of the Arab world, he advocated a moderate and constructive position toward Israel; nonetheless, he supported the rights of the Palestinians and offered the

The Neo-Destour, renamed the Destourian Socialist Party (Parti Socialiste Destourien) in 1964, retained its monopoly over domestic politics. National organizations allowed for some popular mobilization and representation, but by the 1970s liberals within the party became impatient with Bourguiba’s tendency to centralize power in himself. As dissidents within the party broke away to form their own underground political movements in the 1970s, Bourguiba became more authoritarian and detached from the party’s base. Promises of political liberalization failed to materialize. By the 1980s he was convinced that an Islamist revival threatened the country, and, following a series of bomb attacks by Islamist elements on his beloved hometown of Monastir, he ordered a ferocious assault on the leadership and ranks of the Islamic Tendency Movement (Mouvement de la Tendance Islamique). A trial ensued, exposing abuses by the country’s security forces, and Tunisia stood at the brink of political and economic crisis, prompting a constitutional coup that removed Bourguiba on the grounds of ill mental health.

Later years

A charismatic personality, Bourguiba largely remained the father

figure who led Tunisia to independence, although his own popularity had

waned when he became increasingly authoritarian. By actively preventing

the emergence of a successor, he essentially forced his election as

president-for-life in 1975; yet, that his own removal was conducted in a

peaceful and constitutional manner has been seen by both Tunisians and

scholars of the country as a testament to the moderacy and desire for

stability with which he imbued Tunisian politics. At the time of his

ouster, Bourguiba was already age 84 and, despite his failing health,

had ruled the country for 30 years. After his removal from office,

he was confined to his house in Monastir by the new regime and was

permitted only infrequent visitors. His death at home in 2000 after a

period of prolonged illness was marked by a subdued but nonetheless

respectful period of national mourning, and he was buried in his family mausoleum in Monastir.

A charismatic personality, Bourguiba largely remained the father

figure who led Tunisia to independence, although his own popularity had

waned when he became increasingly authoritarian. By actively preventing

the emergence of a successor, he essentially forced his election as

president-for-life in 1975; yet, that his own removal was conducted in a

peaceful and constitutional manner has been seen by both Tunisians and

scholars of the country as a testament to the moderacy and desire for

stability with which he imbued Tunisian politics. At the time of his

ouster, Bourguiba was already age 84 and, despite his failing health,

had ruled the country for 30 years. After his removal from office,

he was confined to his house in Monastir by the new regime and was

permitted only infrequent visitors. His death at home in 2000 after a

period of prolonged illness was marked by a subdued but nonetheless

respectful period of national mourning, and he was buried in his family mausoleum in Monastir.

No comments:

Post a Comment